Frank Grouard on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

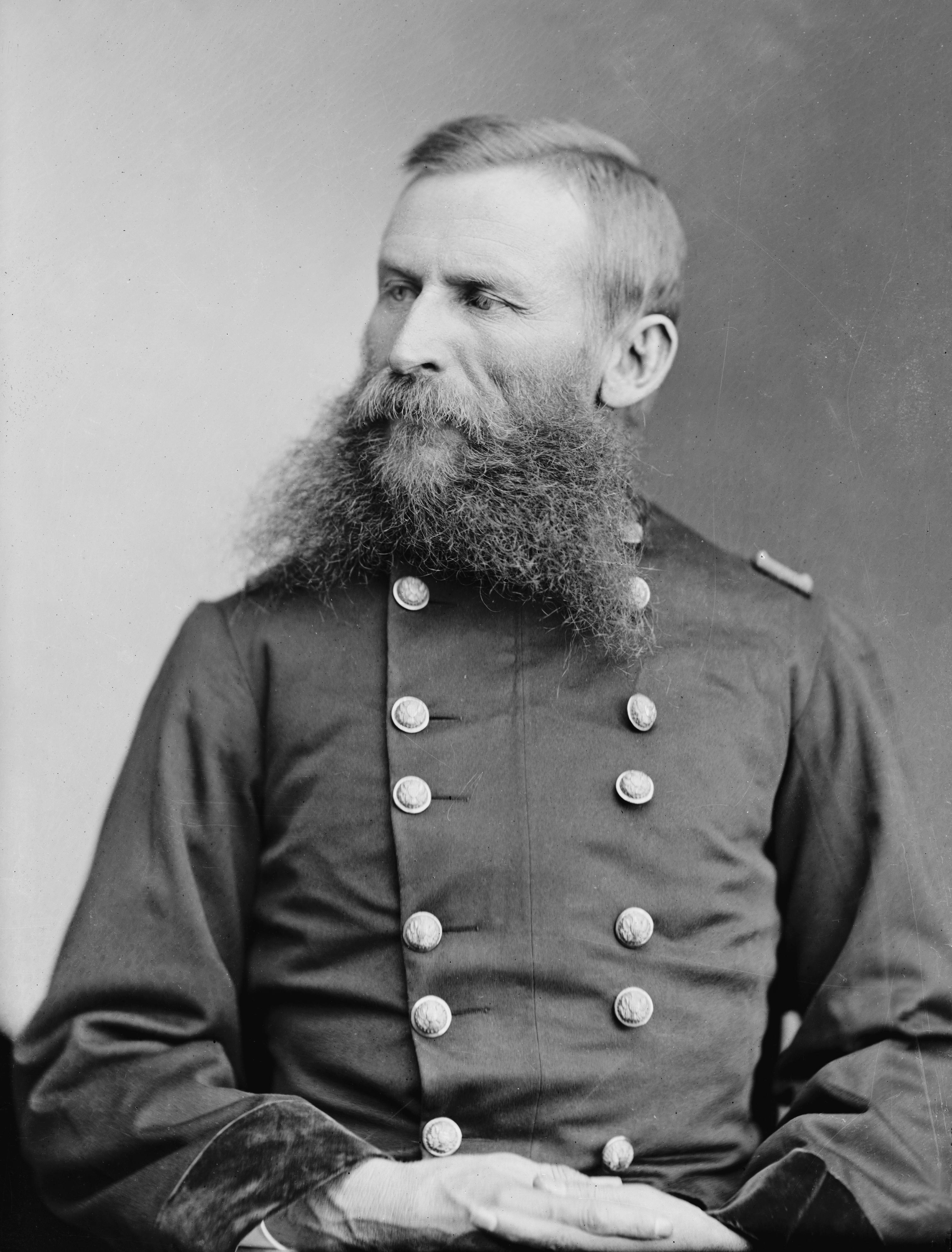

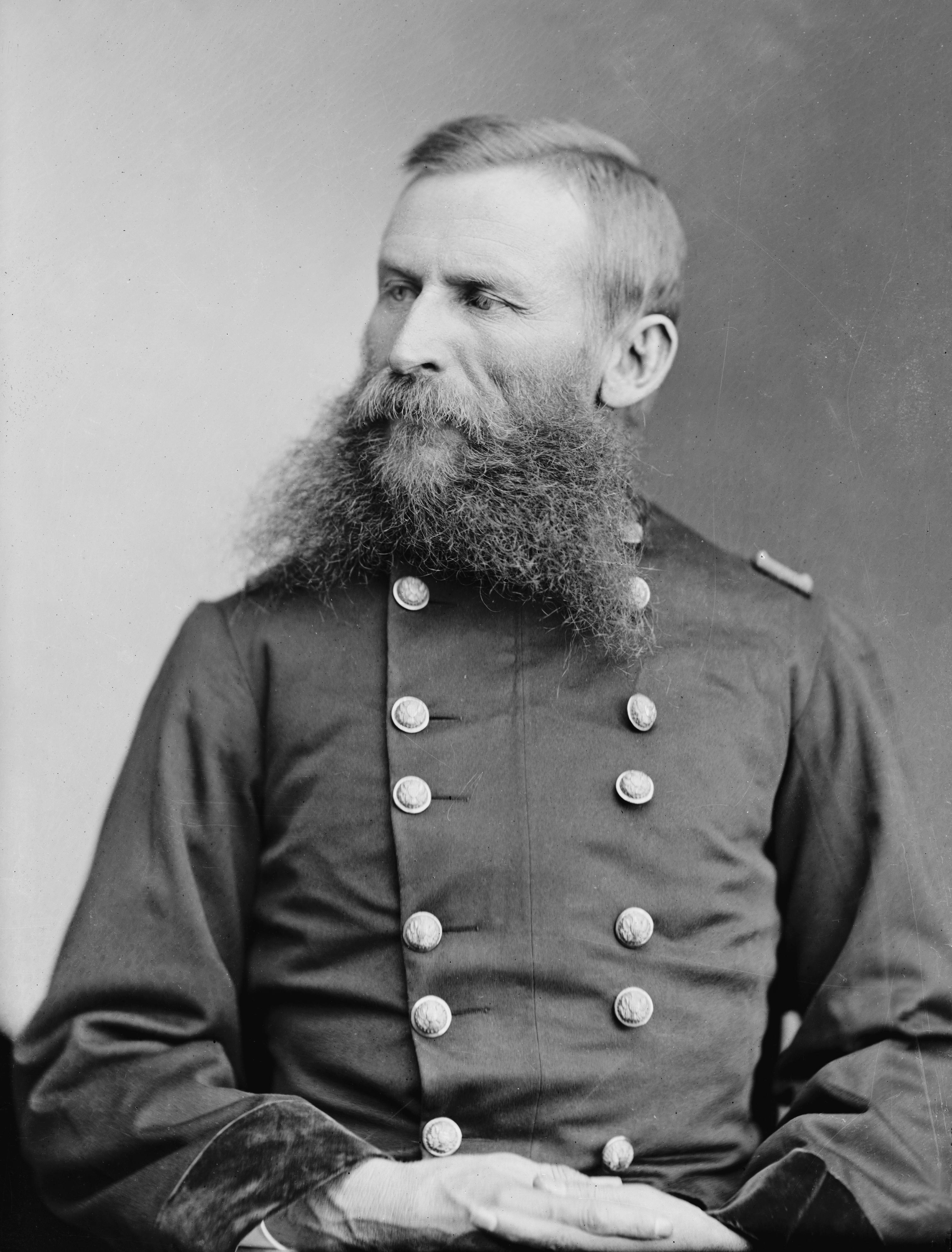

Frank Benjamin Grouard (also known as Frank Gruard and Benjamin Franklin Grouard) (September 20, 1850 – August 15, 1905) was a

In about 1869, while working as a mail carrier, Grouard was captured near the mouth of the Milk River in

In about 1869, while working as a mail carrier, Grouard was captured near the mouth of the Milk River in

When

When

Grouard on Find A Grave

Full text of 'The Life And Adventures of Frank Grouard' by Joe DeBarthe (1894)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Grourad, Frank 1850 births 1905 deaths People of the Great Sioux War of 1876 People from Tahiti People from Beaver County, Utah People from San Bernardino, California French Polynesian emigrants to the United States United States Marshals People from Buffalo, Wyoming

Scout

Scout may refer to:

Youth movement

*Scout (Scouting), a child, usually 10–18 years of age, participating in the worldwide Scouting movement

**Scouts (The Scout Association), section for 10-14 year olds in the United Kingdom

**Scouts BSA, sectio ...

and interpreter for General George Crook

George R. Crook (September 8, 1828 – March 21, 1890) was a career United States Army officer, most noted for his distinguished service during the American Civil War and the Indian Wars. During the 1880s, the Apache nicknamed Crook ''Nantan ...

during the American Indian War of 1876. For the better part of a decade he lived with the Sioux

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin (; Dakota language, Dakota: Help:IPA, /otʃʰeːtʰi ʃakoːwĩ/) are groups of Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribes and First Nations in Canada, First Nations peoples in North America. The ...

tribe before returning to society. He was General Crook's lead scout at the Battle of the Rosebud

The Battle of the Rosebud (also known as the Battle of Rosebud Creek) took place on June 17, 1876, in the Montana Territory between the United States Army and its Crow and Shoshoni allies against a force consisting mostly of Lakota Sioux and Nort ...

Lowe, Percival G. Lowe. (1965). p. 320. ''Five Years A Dragoon ('49 to '54) and Other Adventures on the Great Plains,'' University of Oklahoma Press. participated in the Slim Buttes Fight, Battle of Red Fork, helped to assess the immediate aftermath of the Battle of the Little Bighorn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Nor ...

, and participated in the Wounded Knee Massacre.

Early years

Grouard was aEurasian

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelago ...

born in the Tuamotu Archipelago

The Tuamotu Archipelago or the Tuamotu Islands (french: Îles Tuamotu, officially ) are a French Polynesian chain of just under 80 islands and atolls in the southern Pacific Ocean. They constitute the largest chain of atolls in the world, extendin ...

in the south Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

, to a European father, Benjamin Franklin Grouard

Benjamin Franklin Grouard (January 4, 1819 – March 18, 1894) was one of the earliest Latter Day Saint Mormon missionaries, missionaries to the Society Islands, which now constitute French Polynesia.

Grouard was born in Stratham, New Hampshire, ...

, an American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Tho ...

for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, informally known as the LDS Church or Mormon Church, is a Nontrinitarianism, nontrinitarian Christianity, Christian church that considers itself to be the Restorationism, restoration of the ...

and a Polynesian mother of Asian descent on the island

An island (or isle) is an isolated piece of habitat that is surrounded by a dramatically different habitat, such as water. Very small islands such as emergent land features on atolls can be called islets, skerries, cays or keys. An island ...

of Anaa

Anaa, Nganaa-nui (or Ara-ura) is an atoll in the Tuamotu archipelago, in French Polynesia. It is located in the north-west of the archipelago, 350 km to the east of Tahiti. It is oval in shape, 29.5 km in length and 6.5 km wide, ...

in the South Pacific Ocean; and was the second of three sons born to the Grouard family.

He moved to Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to it ...

with his parents and two brothers in 1852, later moving to San Bernardino

San Bernardino (; Spanish language, Spanish for Bernardino of Siena, "Saint Bernardino") is a city and county seat of San Bernardino County, California, United States. Located in the Inland Empire region of Southern California, the city had a ...

in California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

. After a year in California, Grouard's wife returned to the South Pacific with two of the children, leaving Benjamin with the middle son, Frank. In 1855 he was adopted into the family of Addison

Addison may refer to:

Places Canada

* Addison, Ontario

United States

*Addison, Alabama

*Addison, Illinois

*Addison Street in Chicago, Illinois which runs by Wrigley Field

* Addison, Kentucky

*Addison, Maine

*Addison, Michigan

*Addison, New York

...

and Louisa Barnes Pratt

Louisa Barnes Pratt (November 10, 1802 – September 8, 1880) was a prominent advocate for women's vote and other related causes in the 19th century as well as a Latter-day Saint missionary.

Early life

Louisa Barnes was born in Warwick, Massachus ...

, fellow missionaries for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints with his father. Grouard moved with the Pratt family to Beaver, Utah

Beaver is a city in, and county seat of, Beaver County in southwestern Utah, United States. The population was 3,112 at the 2010 census.

History

Indigenous peoples lived in this area for thousands of years, as shown by archeological evidence ...

, from where he ran away at age 15, moving to Helena, Montana

Helena (; ) is the capital city of Montana, United States, and the county seat of Lewis and Clark County.

Helena was founded as a gold camp during the Montana gold rush, and established on October 30, 1864. Due to the gold rush, Helena would ...

and becoming an express rider and stage driver.

Indian scout

In about 1869, while working as a mail carrier, Grouard was captured near the mouth of the Milk River in

In about 1869, while working as a mail carrier, Grouard was captured near the mouth of the Milk River in Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbi ...

by Crow Indians

The Crow, whose autonym is Apsáalooke (), also spelled Absaroka, are Native Americans living primarily in southern Montana. Today, the Crow people have a federally recognized tribe, the Crow Tribe of Montana, with an Indian reservation loca ...

who took all his possessions and abandoned him in a forest where he was found by Sioux Indians and later adopted as a brother by Chief Sitting Bull

Sitting Bull ( lkt, Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake ; December 15, 1890) was a Hunkpapa Lakota leader who led his people during years of resistance against United States government policies. He was killed by Indian agency police on the Standing Rock I ...

. He was probably accepted by them as an Indian because his Polynesia

Polynesia () "many" and νῆσος () "island"), to, Polinisia; mi, Porinihia; haw, Polenekia; fj, Polinisia; sm, Polenisia; rar, Porinetia; ty, Pōrīnetia; tvl, Polenisia; tkl, Polenihia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, made up of ...

n features resembled those of the Sioux. Grouard married a Sioux woman and learned to speak the Sioux language

Sioux is a Siouan language spoken by over 30,000 Sioux in the United States and Canada, making it the fifth most spoken indigenous language in the United States or Canada, behind Navajo, Cree, Inuit languages, and Ojibwe.

Regional variation

Si ...

fluently, taking the Indian names 'Sitting-with-Upraised-Hands' and 'Standing Bear', (Yugata), as he had been captured wearing a bearskin coat. For seven to eight years he lived in the camps of Sitting Bull

Sitting Bull ( lkt, Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake ; December 15, 1890) was a Hunkpapa Lakota leader who led his people during years of resistance against United States government policies. He was killed by Indian agency police on the Standing Rock I ...

and Crazy Horse

Crazy Horse ( lkt, Tȟašúŋke Witkó, italic=no, , ; 1840 – September 5, 1877) was a Lakota war leader of the Oglala band in the 19th century. He took up arms against the United States federal government to fight against encroachment by wh ...

until he managed to escape, becoming an emissary of the Indian Peace Commission

The Indian Peace Commission (also the Sherman, Taylor, or Great Peace Commission) was a group formed by an act of Congress on July 20, 1867 "to establish peace with certain hostile Indian tribes." It was composed of four civilians and three, la ...

at Red Cloud Agency

The Red Cloud Agency was an Indian agency for the Oglala Lakota as well as the Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho, from 1871 to 1878. It was located at three different sites in Wyoming Territory and Nebraska before being moved to South Dakota. It w ...

in Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the southwe ...

. In 1876, Grouard became a Chief Indian Scout in the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

under General George Crook

George R. Crook (September 8, 1828 – March 21, 1890) was a career United States Army officer, most noted for his distinguished service during the American Civil War and the Indian Wars. During the 1880s, the Apache nicknamed Crook ''Nantan ...

, fighting Sioux Indians. By February 1876, many Indians were leaving the reservations with some refusing to return when ordered to by the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

government. General Crook began his winter march from Fort Fetterman on March 1, 1876 with many companies of troops and with Grouard as his Chief Indian scout

Scout may refer to:

Youth movement

*Scout (Scouting), a child, usually 10–18 years of age, participating in the worldwide Scouting movement

**Scouts (The Scout Association), section for 10-14 year olds in the United Kingdom

**Scouts BSA, sectio ...

and interpreter.

Indian Wars

When

When Sitting Bull

Sitting Bull ( lkt, Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake ; December 15, 1890) was a Hunkpapa Lakota leader who led his people during years of resistance against United States government policies. He was killed by Indian agency police on the Standing Rock I ...

heard that Grouard was Crook's Chief Scout, he saw an opportunity to kill him in battle. By March 17, 1876, Grouard had located He Dog's (Lakota) and Old Bear's (Cheyenne) combined village on Powder River in Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbi ...

. He followed the trail left by two hostiles, who had been spotted the previous day, all through the night, even when their tracks were covered during a snowstorm. General Crook, in his May 1876 report wrote, "I would sooner lose a third of my command than Frank Grouard!"DeBarthe, p. 18 Other scouts, jealous of Crook's preference for Grouard, tried to turn the General against him by claiming that Grouard had joined up as a scout in order to lead the Army into a carefully orchestrated trap, but Crook saw through all this. On occasions when scouting Grouard would dress as an Indian so that genuine Indians would take no notice of him. Thus, Grouard could pass as an American and an American Indian.

He was a major participant in the Rosebud campaign, and saw action in the Battle of the Rosebud

The Battle of the Rosebud (also known as the Battle of Rosebud Creek) took place on June 17, 1876, in the Montana Territory between the United States Army and its Crow and Shoshoni allies against a force consisting mostly of Lakota Sioux and Nort ...

. General George Crook

George R. Crook (September 8, 1828 – March 21, 1890) was a career United States Army officer, most noted for his distinguished service during the American Civil War and the Indian Wars. During the 1880s, the Apache nicknamed Crook ''Nantan ...

and his officers, having retreated from the Rosebud, were hunting in the foothills of the Bighorns when Grouard, known to the Brulé

The Brulé are one of the seven branches or bands (sometimes called "sub-tribes") of the Teton (Titonwan) Lakota American Indian people. They are known as Sičhą́ǧu Oyáte (in Lakȟóta) —Sicangu Oyate—, ''Sicangu Lakota, o''r "Burnt ...

as 'One-Who-Catches' and to the Hunkpapa

The Hunkpapa (Lakota: ) are a Native American group, one of the seven council fires of the Lakota tribe. The name ' is a Lakota word, meaning "Head of the Circle" (at one time, the tribe's name was represented in European-American records as ...

as 'Standing Bear', was acting as guide. Between 9 and 10 in the morning of June 25, 1876 Crook

Crook is another name for criminal.

Crook or Crooks may also refer to:

Places

* Crook, County Durham, England, a town

* Crook, Cumbria, England, village and civil parish

* Crook Hill, Derbyshire, England

* Crook, Colorado, United States, a ...

's forces were in Goose Creek Valley when Grouard saw the smoke from Indian signal fires in the distance, which indicated that George Armstrong Custer

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the American Indian Wars.

Custer graduated from West Point in 1861 at the bottom of his class, b ...

's command was engaged with the enemy, outnumbered, and being badly pressed. The officers present used their field glasses but could make no sense of the smoke signals and laughed at the idea that a half-Indian could have such knowledge of their meaning. To prove that he was right, at noon Grouard mounted his horse and rode towards the signals, reaching the Little Bighorn, a distance of some seventy miles, at 11 pm on June 25. Here he discovered the bodies of the slain before being chased back to Goose Creek by hostiles, bringing the news of Custer

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the American Indian Wars.

Custer graduated from West Point in 1861 at the bottom of his class, b ...

's death to Crook

Crook is another name for criminal.

Crook or Crooks may also refer to:

Places

* Crook, County Durham, England, a town

* Crook, Cumbria, England, village and civil parish

* Crook Hill, Derbyshire, England

* Crook, Colorado, United States, a ...

.

Crazy Horse

Grouard has been blamed by some as being instrumental in the subsequent death ofCrazy Horse

Crazy Horse ( lkt, Tȟašúŋke Witkó, italic=no, , ; 1840 – September 5, 1877) was a Lakota war leader of the Oglala band in the 19th century. He took up arms against the United States federal government to fight against encroachment by wh ...

. In August 1877, officers at Camp Robinson received word that the Nez Perce

The Nez Percé (; autonym in Nez Perce language: , meaning "we, the people") are an Indigenous people of the Plateau who are presumed to have lived on the Columbia River Plateau in the Pacific Northwest region for at least 11,500 years.Ames, K ...

of Chief Joseph

''Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt'' (or ''Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it'' in Americanist orthography), popularly known as Chief Joseph, Young Joseph, or Joseph the Younger (March 3, 1840 – September 21, 1904), was a leader of the Wal-lam-wat-kain (Wallowa ...

had broken out of their reservations in Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyom ...

and were fleeing north through Montana toward Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

. When asked by Lieutenant Clark to join the Army against the Nez Perce, Crazy Horse and the Miniconjou

The Miniconjou (Lakota: Mnikowoju, Hokwoju – ‘Plants by the Water’) are a Native American people constituting a subdivision of the Lakota people, who formerly inhabited an area in western present-day South Dakota from the Black Hills i ...

leader Touch the Clouds

Touch the Clouds ( Lakota: Maȟpíya Ičáȟtagya or Maȟpíya Íyapat'o) (c. 1838 – September 5, 1905) was a chief of the '' Minneconjou'' Teton Lakota (also known as Sioux) known for his bravery and skill in battle, physical strength and ...

objected, saying that they had promised to remain at peace when they surrendered. According to one version of events, Crazy Horse finally agreed, saying that he would fight "till all the Nez Perce were killed". But his words were apparently misinterpreted, perhaps deliberately, by Grouard, who reported that Crazy Horse had said that he would "go north and fight until not a white man is left". When he was challenged over his interpretation, Grouard left the council. Grouard claimed that he was present when Crazy Horse was killed.

Grouard was also present at the Yellowstone Expeditions and the Battle of Slim Buttes. He was assigned to the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation

The Pine Ridge Indian Reservation ( lkt, Wazí Aháŋhaŋ Oyáŋke), also called Pine Ridge Agency, is an Oglala Lakota Indian reservation located entirely within the U.S. state of South Dakota. Originally included within the territory of the Gr ...

during the Ghost Dance Uprising and was present at the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890. Grouard later served as a U.S. Marshal

The United States Marshals Service (USMS) is a federal law enforcement agency in the United States. The USMS is a bureau within the U.S. Department of Justice, operating under the direction of the Attorney General, but serves as the enforce ...

in Fort McKinney, Buffalo, Wyoming

Buffalo is a city in Johnson County, Wyoming, United States. The city is located almost equidistant between Yellowstone Park and Mount Rushmore. The population was 4,415 at the 2020 census, down from 4,585 at the 2010 census. It is the county s ...

and was involved in the Johnson County War

The Johnson County War, also known as the War on Powder River and the Wyoming Range War, was a range conflict that took place in Johnson County, Wyoming from 1889 to 1893. The conflict began when cattle companies started ruthlessly persecuting ...

of 1892.

Killing of an outlaw

In 1878, Grouard received a message from Montana Sheriff Tom Irvine that two Wyoming men had stolen horses in Yellowstone, and to be on the look out for them. Grouard took off for O'Malley'sdance hall

Dance hall in its general meaning is a hall for Dance, dancing. From the earliest years of the twentieth century until the early 1960s, the dance hall was the popular forerunner of the discothèque or nightclub. The majority of towns and citi ...

, located a couple miles from the fort and noticed a crowd of people around it. He noticed a man by the name of McGloskey, a possible army deserter

Desertion is the abandonment of a military duty or post without permission (a pass, liberty or leave) and is done with the intention of not returning. This contrasts with unauthorized absence (UA) or absence without leave (AWOL ), which ...

, riding one of the stolen horses. Both McGloskey and Grouard knew each other well, with McGloskey making "threats a hundred times during the year that he would kill me on sight." With his carbine

A carbine ( or ) is a long gun that has a barrel shortened from its original length. Most modern carbines are rifles that are compact versions of a longer rifle or are rifles chambered for less powerful cartridges.

The smaller size and lighter ...

in one hand, Grouard tried to wave McGloskey to a stop with the other. McGloskey put spurs to his horse and as he rode past Grouard he fired his revolver

A revolver (also called a wheel gun) is a repeating handgun that has at least one barrel and uses a revolving cylinder containing multiple chambers (each holding a single cartridge) for firing. Because most revolver models hold up to six roun ...

at him, barely missing people in the crowd. When he got a hundred yards near the end of town, he stopped his horse for another shot, but Grouard shot him off his horse with his carbine. Frank made a quick stop at the wounded outlaw who was being attended to by one of the spectators, saw that he was still alive, then proceeded upon a fourteen mile chase for his partner, who ended up escaping. McGloskey cursed out Grouard until his last breath, stating that he just wanted to live long enough to get one more shot at him; Grouard replied, that "he could have the first shot...He died that night at eight o'clock hurling curses at me with his very last breath.

Marriage, family and later years

By 1893, Frank Grouard had become famous, and his father,Benjamin Franklin Grouard

Benjamin Franklin Grouard (January 4, 1819 – March 18, 1894) was one of the earliest Latter Day Saint Mormon missionaries, missionaries to the Society Islands, which now constitute French Polynesia.

Grouard was born in Stratham, New Hampshire, ...

, who hadn't seen his son since 1855, read of the publication of a biography of the scout. Benjamin Grouard then travelled to Sheridan, Wyoming

Sheridan is a town in the U.S. state of Wyoming and the county seat of Sheridan County. The town is located halfway between Yellowstone Park and Mount Rushmore by U.S. Route 14 and 16. It is the principal town of the Sheridan, Wyoming, Micropol ...

, where he immediately recognized his son despite a forty-year separation. Frank was married in Amazonia, Missouri

Amazonia is a village in Lincoln Township, Andrew County, Missouri, United States. The population was 312 at the 2010 census. It is part of the St. Joseph, MO– KS Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

Amazonia was laid out in 1857. A pos ...

on April 10, 1895 to Lizabell "Belle" Ostrander (1862-1912). At least one son, possibly two, seem to have been the result of this union, Benjamin Franklin Grouard, also known as Frank B. Grouard Jr., born in St. Joseph, Missouri on May 15, 1896. The marriage seems to have been brief or Frank was mostly absent from his wife and family for public records primarily list his wife and sons as living with the latter's parents. Grouard's son Benjamin F. Grouard was married at St. Joseph, Missouri on November 28, 1912 to Ethel M. Poe. The later fate of him remains unknown.

In 1893 the U.S. Government needed a mail

The mail or post is a system for physically transporting postcards, letter (message), letters, and parcel (package), parcels. A postal service can be private or public, though many governments place restrictions on private systems. Since the mid ...

route for the growing population of Wyoming and surrounding area beginning with a route from Sheridan to Hyattville, over the Big Horn Mountains

The Bighorn Mountains ( cro, Basawaxaawúua, lit=our mountains or cro, Iisaxpúatahchee Isawaxaawúua, label=none, lit=bighorn sheep's mountains) are a mountain range in northern Wyoming and southern Montana in the United States, forming a nort ...

. The worst winter months in that portion of the mountains was February and March, and it was in March that Grouard received his marching orders to find that route. With a volunteer Wyoming man nick-named "Shorty", along with guns, blankets, and rations for five days they started out. Forced to leave their horses at the Big Horn iver? they took to ''snowshoes

Snowshoes are specialized outdoor gear for walking over snow. Their large footprint spreads the user's weight out and allows them to travel largely on top of rather than through snow. Adjustable bindings attach them to appropriate winter footwe ...

'' and headed for the divide. Snowed in at 13,000 feet above sea level, they spent three of their eight days there without fire or food. But their mission had been accomplished, they reached Hyattville, and the mail route was accepted and laid out as Grouard had indicated it. However, Frank had suffered permanent eye damage from the snow and frost, and spent the rest of his life "consult ngeminent specialists concerning his eyesight

Visual perception is the ability to interpret the surrounding environment through photopic vision (daytime vision), color vision, scotopic vision (night vision), and mesopic vision (twilight vision), using light in the visible spectrum reflecte ...

." "''Shorty'' had suffered the same, with frozen face, hands and feet."

Frank Grouard died at St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the Greater St. Louis, ...

in 1905 where he was eulogized as a "scout of national fame". He was buried with full military honors at Ashland Cemetery in Saint Joseph, Missouri.

In fiction

Grouard appears in ''Flashman and the Redskins

''Flashman and the Redskins'' is a 1982 novel by George MacDonald Fraser. It is the seventh of the Flashman novels.

Plot introduction

Presented within the frame of the supposed discovery of a trunkful of papers detailing the long life and care ...

'' by George MacDonald Fraser

George MacDonald Fraser (2 April 1925 – 2 January 2008) was a British author and screenwriter. He is best known for a series of works that featured the character Flashman.

Biography

Fraser was born to Scottish parents in Carlisle, England, ...

as the illegitimate son of Flashman and Cleonie Grouard, Flashman's mistress and a slave and prostitute

Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, non-penet ...

. Fraser has Grouard being brought up by Indians after Flashman sells his pregnant mother Cleonie to the Navajo

The Navajo (; British English: Navaho; nv, Diné or ') are a Native American people of the Southwestern United States.

With more than 399,494 enrolled tribal members , the Navajo Nation is the largest federally recognized tribe in the United ...

. In the story, the Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

-educated Grouard rescues Flashman during the Battle of the Little Bighorn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Nor ...

while fighting against the American Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

as a Sioux

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin (; Dakota language, Dakota: Help:IPA, /otʃʰeːtʰi ʃakoːwĩ/) are groups of Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribes and First Nations in Canada, First Nations peoples in North America. The ...

.

On television

Theactor

An actor or actress is a person who portrays a character in a performance. The actor performs "in the flesh" in the traditional medium of the theatre or in modern media such as film, radio, and television. The analogous Greek term is (), li ...

Bruce Kay, who appeared only five times on screen between 1955 and 1958, played Grouard in the 1958 episode, "The Greatest Scout of All", on the syndicated anthology series

An anthology series is a radio, television, video game or film series that spans different genres and presents a different story and a different set of characters in each different episode, season, segment, or short. These usually have a differ ...

''Death Valley Days

''Death Valley Days'' is an American old-time radio and television anthology series featuring true accounts of the American Old West, particularly the Death Valley country of southeastern California. Created in 1930 by Ruth Woodman, the program ...

'', hosted by Stanley Andrews

Stanley Andrews (born Stanley Martin Andrzejewski; August 28, 1891 – June 23, 1969) was an American actor perhaps best known as the voice of Daddy Warbucks on the radio program ''Little Orphan Annie'' and later as "The Old Ranger", the first ...

. Frank Richards (1909-1992) was cast in the same episode as Sitting Bull

Sitting Bull ( lkt, Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake ; December 15, 1890) was a Hunkpapa Lakota leader who led his people during years of resistance against United States government policies. He was killed by Indian agency police on the Standing Rock I ...

. In the story line, the half Sioux Grouard is caught in a culture clash but becomes a highly regarded scout for the United States Army, who is dispatched on the toughest of assignments.

References

External links

*Grouard on Find A Grave

Full text of 'The Life And Adventures of Frank Grouard' by Joe DeBarthe (1894)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Grourad, Frank 1850 births 1905 deaths People of the Great Sioux War of 1876 People from Tahiti People from Beaver County, Utah People from San Bernardino, California French Polynesian emigrants to the United States United States Marshals People from Buffalo, Wyoming